Situational Models of Implicit Bias

The Bias of Crowds model (Payne et al., 2017) suggests that (implicit) bias is determined by the social, cultural and physical environment. The model is supported by a wide range of research findings, linking implicit bias on a geographical level such as counties or states with differences in the social, cultural, or physical environment. If different environments are associated with different levels of implicit bias, it follows that changes in the environment should causally affect implicit bias.

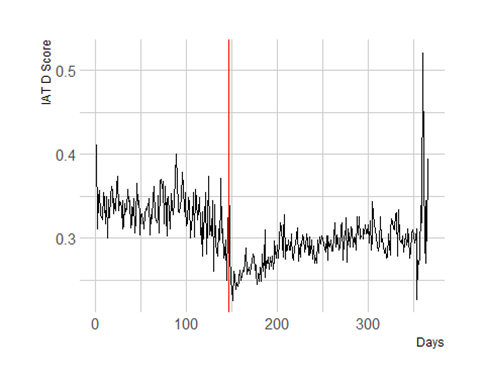

In my first project in this research line we used multi-level analyses and Directed Acyclic Graphs (a causal inference tool) to investigate whether the 2020 BLM protests led to changes in implicit bias over time. We found that there was a massive drop in implicit bias right after the onset of the protests - with implicit bias steadily increasing again once attention to BLM faded ((Primbs, Holland, Oude Maatman, Lansu, Faure, & Bijlstra, accepted at PSPB)).

In a second project, built on an incidental finding in the BLM paper, we show that implicit bias towards racial and ethnic minorities is increased during Christmas (Primbs, Connor, Holland, Peetz, Dudda, Faure, & Bijlstra, under review), while implicit bias towards religious and sexual minorities is decreased. In a follow-up experimental study funded by the Centre for Adversarial Collaborations, we assessed the same people both on Christmas and two weeks later and found that the effect of the experiment are not in line with the effects found in the Project Implicit data. This illustrates methodological problems that arise when using online databases that are open for self-selection and highlights concerns about aggregated implicit bias measures as proof of the causal role of the environment on people’s implicit biases.

In a third project, we re-examine the relationship between Confederate monuments and implicit bias. First, using Project Implicit data we show that there is no correlation between the presence of a Confederate monument and implicit bias, directly contradicting previous research on a much smaller sample (Vuletich & Payne, 2019). Second, we use sophisticated fixed effects models to investigate the effect of the removal of Confederate monuments on implicit bias and find that the removal of a Confederate monument in a region does not affect implicit bias. Third, we use standard priming experiments to show that exposing people to Confederate monuments does not affect their implicit bias scores, except if we explain the meaning of the Confederate monuments to them first. Lastly, we conduct a field experiment on colonial monuments in the Netherlands and show that exposure to colonial monuments only increase implicit bias if we explain the historical meaning of the colonial monuments to participants. In sum, this study shows (a) that historical markers of inequality only affect implicit bias if people are aware that a marker indeed marks inequality and (b) that adding historical background information to colonial or Confederate monuments may have undesirable consequences (Primbs, Sommet, Bijlstra, Payne, Faure, Lansu, Holland, Diekman, & Vuletich, in preparation).

In a fourth project, we investigated the association between historical Ku Klux Klan presence and implicit bias (Primbs, Wienk, Holland, Calanchini, & Bijlstra, under review). Building on situational models of bias we hypothesized that higher levels of historical Klan presence are associated with higher levels of modern-day implicit bias. However, we find across many analyses and datasets that historical Ku Klux Klan presence is robustly linked to lower levels of implicit racial bias, which forces us to think about bias and systemic inequalities in a completely novel manner: When and why is historical inequality associated with higher as opposed to lower levels of bias? And what can these differences teach us about designing interventions?